How We Got Here

The history of how the settlement movement dominated Israel's priorities, torpedoed peace, and drove the cycle of violence.

“The Jewish people have an exclusive and indisputable right to all areas of the Land of Israel. The government will promote and develop settlement in all parts of the Land of Israel in the Galilee, the Negev, the Golan, Judea and Samaria.” So reads the first among the list of guiding principles Israel’s governing coalition formally announced upon taking power in late 2022 (source, translation).

This conviction that Jews have an exclusive claim to all the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River is not new. It is both the cause and culmination of Israel’s decades-long settlement movement and the accompanying military occupation, which has left Palestinians, who comprise half of the land’s population, largely without rights. Palestinians have resisted this reality, but instead of recognizing this resistance as a result of its fundamental political contradiction—the desire to be both democratic and predominantly Jewish—Israel, a country with a liberal self-image, historical trauma, and diplomatic considerations, chose to frame it as a security problem.

By accepting this security framing, the international community mistakenly believed that Israel would naturally gravitate towards peace if only given sufficient security guarantees. In reality, any meaningful peace agreement would have threatened Israel’s greater priority: expanding settlements. Had the world recognized this dynamic, it could have forced Israel to cease construction and created the conditions under which sustainable peace might be possible. Failing to do so not only prevented the success of the peace process, but led inexorably to calamity.

Author’s Note:

This essay adopts a Zionist framing in order to discuss decades of policy that took the legitimacy of a Jewish nation state as a given. Adoption is not endorsement. There are important reasons to challenge the notion that one group of people ever had the right to form their own country on land they shared with another group of people in the first place. That discussion can exist in parallel with, but is separate from, the argument offered here, so I request readers’ permission to address it in a future essay.

Similarly, this essay omits discussion of the beginning of the conflict: the approximately 70 years leading up to the formation of Israel in 1948, the resulting expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians, and the immediate aftermath. This history is important, but not immediately relevant to this particular thesis.

Settlements

The existence and continued growth of the settlements prove that Israel prioritizes territorial expansion over long-term security. Incentivizing hundreds of thousands of civilians to build their homes in occupied territory makes little sense for a country that may at some point wish to trade land for a sustainable peace agreement. A deep nationalist impulse to claim as its own many of the most significant landmarks in Jewish biblical history, not defense strategy, best explains Israel’s settlement policy. This ideological motivation, soon to be bolstered by economic interest, rapidly established the foundation for a politically-dominant colonialist movement.

By the close of the 1967 war, Israel’s security interests ostensibly motivated its continued control over East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza: It wished to increase the amount of land a foreign army would have to cross to reach Israel’s center. It did not limit construction in occupied territory to military installations, however. It began transplanting civilians.

Israel’s Labor government built the first settlements in 1968, with the “objective to secure a Jewish majority in key strategic regions of the West Bank” according to the Jewish Virtual Library. The first explicitly ideological settlers moved into Hebron the same year. Just four years later, the settler population reached 10,608. The majority lived not in militarily advantageous territory near the Jordan River, but in East Jerusalem, which Israel formally annexed in 1980, a clear violation of International Law, and an action no other country has officially recognized.

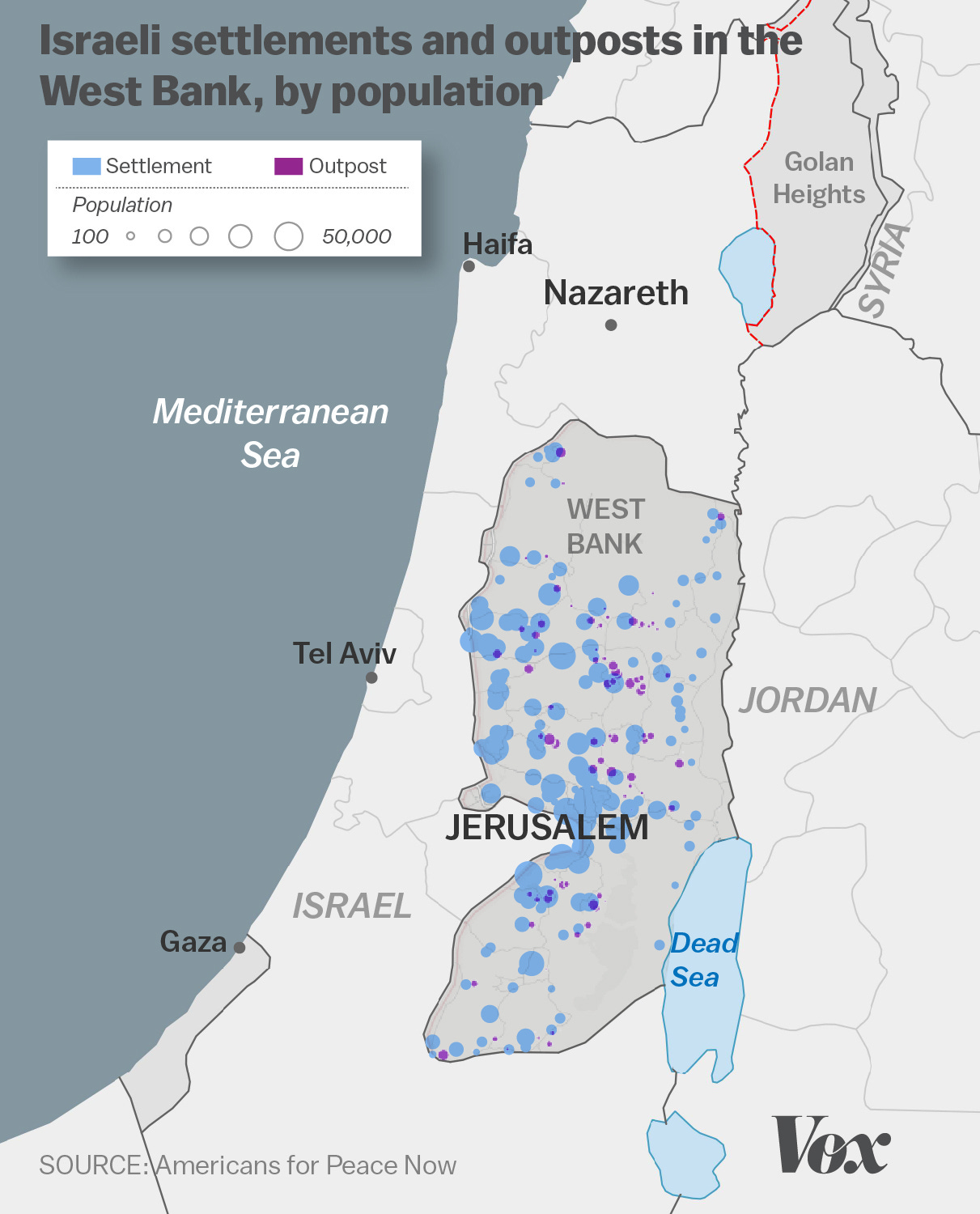

The pace of construction exploded after the 1977 election of Menachem Begin, whose Likud Party was founded on the principle that “Judea and Samaria [the ideological terminology for the West Bank] will not be handed to any foreign administration; between the [Mediterranean] Sea and the Jordan [River] there will only be Israeli sovereignty.” The Begin administration and subsequent Likud governments subsidized construction and provided financial incentives to Jewish families moving to Israel’s new colonies: $300 million (USD) per year in the 1980s, which the government increased to $1 billion in the early 90s.1 The settler population has since grown in almost perfect linear fashion–regardless of which party controlled the Knesset (parliament)–reaching more than 700,000 today, with 220,000 in East Jerusalem (2020) and 517,000 in the West Bank (2023).

The population numbers alone don’t convey the degree to which Israel solidified territorial control. One could imagine Israel concentrating settlements near the 1967 armistice line in order to accommodate population growth without precluding a future peace agreement. That isn’t what happened. Consider the following map:

The political map mimics the geographic one. As more Israelis moved into settlements, their political representation expanded. Today, nearly 8% of Israeli voters live in occupied territory and naturally consider the maintenance and growth of their communities a major political priority. Pro-settlement parties dominate Israel’s current governing coalition: Likud, The Religious Zionist Party, Jewish Power, Shas, and Noam all firmly support settlement construction.

Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has spent his many years in office gradually making his intention to annex the West Bank more explicit. Israeli lawyer Michael Sfard published an article in Foreign Policy early last year describing the steps Netanyahu’s far-right coalition was taking towards full annexation. In late 2017, his government passed declaratory legislation instructing Likud legislators to pursue annexation. In 2019, he articulated a policy of gradually applying Israeli sovereignty to the occupied territories. The coalition agreement Netanyahu signed with the Religious Zionist Party in late 2022 is particularly direct: “The Prime Minister will work towards the formulation and promotion of a policy whereby sovereignty is applied to the Judea and Samaria.”

By encouraging average Israelis to build their lives in settlements, the early supporters of the settlement movement created an inescapable political center of gravity. They tied common community needs, like building new schools and hospitals, to any discussion about restricting settlement growth. Because of this dynamic, even Israeli politicians inclined to make large territorial compromises nevertheless approved more settlement construction, increasing the proportion of the population that supported further growth. For this reason, the political power of the movement has reliably outpaced the pressure to end it.

Apartheid

Almost no one disputes that Israel practices apartheid, they merely disagree on what to call it.

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court defines apartheid as, “the implementation and maintenance of a system of legalized racial segregation in which one racial group is deprived of political and civil rights.” The difference between military occupation–which the world recognizes as a legitimate activity–and the ICC definition recounted above rests on the word “maintenance.” A military occupation is meant to be temporary. Apartheid is indefinite.

“Occupation” is the word the world uses to describe Israel’s control of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. The associated narrative is indeed one of impermanence: most folks maintain a vague assumption that at least some of the land will be returned to someone, eventually. But Israel's behavior since the end of the 1967 war and the official position of its recent governments show that much of its leadership always intended to control these territories permanently.

Permanent control requires permanent military occupation. There isn’t any other paradigm under which nearly a million Israeli citizens could live in cities and towns connected by Israeli highways, served by Israeli utilities, and governed by Israeli law without actually living within Israel. The occupation is apartheid because the settlements require it to be permanent.

Apartheid in structure is apartheid in experience.

In Jerusalem, Israel uses myriad bureaucratic mechanisms to remove Palestinians from their homes. It regularly cancels the residency permits of Palestinian Jerusalemites when they live outside of the city for extended periods, then confiscates their properties under its “Absentee Property” law. Friends of the author hide their American citizenship from the Israeli government and feel obligated to visit home every few months for exactly this reason. The formula Israel uses to determine whether to cancel residency is unclear and ever-changing.

This policy has precedent: in 2012, Israel publicly acknowledged canceling the residencies of 240,000 Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza between 1967 and 1994. These people often arrived at the airport to be told they no longer had the right to enter the land in which they grew up.

The Jerusalem municipality actively promotes housing construction for Jews while constraining it for Palestinians. City authorities have initiated planning and sought tenders for 55,000 housing units in Jewish neighborhoods in occupied East Jerusalem since 1967, but have only initiated 600 for Palestinians, despite the latter composing most of the population (from approximately 100% in 1967 to 60% in 2021). Between 1991 and 2018, Jewish residents received permits for more than twice as many housing units as Palestinian residents (21,834 vs. 9,536). Israeli authorities currently demolish around 200 Palestinian units per year—20,000 are under threat of demolition—arguing that they were built illegally (largely because the city makes it so difficult for Palestinians to build legally).2

In the West Bank, Palestinians are forbidden from using much of the infrastructure Israel built to let settlers travel between the settlements, and the Israeli military frequently and unpredictably blocks the “approved” routes between Palestinian cities. Palestinians may not travel abroad without Israeli approval. Israel controls Palestinian water and electromagnetic spectrum (for mobile networks). The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) regularly conducts raids into Palestinian population centers, and often holds detainees indefinitely without issuing formal charges. Jewish settlers frequently attack Palestinian homes and farms, sometimes under IDF protection.

Megan Stack vividly illustrates this reality in her 9 December essay in the New York Times. She joins two Palestinian men as they return to their village after fleeing a gang of Jewish settlers who destroyed a small medical clinic, burned down parts of the schoolhouse, and rampaged through family homes. They find an official from Israel’s Civil Administration waiting for them. The encounter is worth quoting in full:

How did he know we were coming?” the village head, Fayez Til, told me he wondered as he walked over to the official. Mr. Til was plainly dressed and distinctly unarmed, in comparison with his visitor. He speaks Hebrew and studied nursing at Hebron University and treated patients at the village clinic before the settlers started marauding.

The uniformed visitor laid down the law in soft, even tones: If you insist on coming home, he told Mr. Til with an air of generosity, you can — so long as you accept its trashed condition. “It’s as is,” he said, as if he were selling a house. Army drones had photographed every detail, he explained. If the residents moved so much as a stone or pulled a tarp over an unroofed house, it would be considered an illegal construction, and there could be trouble.

Mr. Til and the others were incredulous. They pressed: What if it rains? What about the summer sun? The official held firm: You move things, you put up a tarp, you break the law. And then, having delivered this discouraging welcome, he drove off.

Apartheid in Gaza mirrored conditions in the West Bank until Israel removed the 8,000 settlers who lived there in 2005. Without the need to support the settlements, direct occupation was no longer necessary, and it instead focused on controlling movement of goods and people into and out of the Strip. To understand what happened next, it’s critical to consider the impact of the peace process.

Peace Negotiations

The goal of this section is not to provide an exhaustive account of the peace process—historians have much more to say about the intentions, strategy, optimism, dishonesty and internal politics of both parties during this period—but to demonstrate the role settlements played. The fundamental formula for any peace agreement would involve relinquishing land to Palestinians in exchange for security. By not insisting that settlement construction stop as a precondition for negotiations, the United States, which mediated the process, created a dynamic that strongly incentivized Israel to continue taking more land while those negotiations took place. This incrementally empowered the Israeli right and convinced Palestinians that peace talks were cover for further dispossession.

In late 1987, the whole of Palestinian society rose up to challenge occupation. Civil disobedience, labor strikes, riots, and images on TV of Israeli soldiers detaining and breaking the arms of stone-throwing teenagers forced the International Community to address Palestinian grievances. U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz proposed an initiative modeled on the successful 1982 Camp David agreement between Israel and Egypt. The parties would negotiate a solution based on UN Resolution 242, which calls for Israel’s full withdrawal from the territories it occupied in 1967. Shultz advocated for the parties to negotiate both the transitional period and the final status agreement as part of one process.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who fundamentally opposed the idea of returning land to Palestinians in exchange for peace,3 objected to the Shultz Initiative, insisting that any discussion of final status be dependent on the success of the transitional period. Israel stood to gain the most from “transitional” measures, such as the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) officially recognizing Israel and making commitments to prevent attacks on Israel. Final status questions, by contrast, included the fate of settlements and borders, discussions about which threatened the territorial ambitions of Shamir’s Likud party.

This pattern of engaging on matters of security, economic, and governance, while avoiding discussions about relinquishing territory and demarcating borders characterized the following two decades of diplomatic engagement between the parties. The landmark Oslo Accords, negotiated by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat between 1993 and 1995, provided for a five-year transitional period, during which the PLO would be allowed to return to Gaza and the West Bank city of Jericho to begin building state institutions. Later, Israel agreed to withdraw from large Palestinian cities in the West Bank, including Ramallah, Nablus, Bethlehem, and Jenin, allowing the new Palestinian Authority to take over responsibility for those communities. To comply with the requirements of the agreement, Arafat built a 40,000-strong professional security force, trained and supplied largely by the United States, which would coordinate with Israeli security to prevent terrorist attacks on Israel.

However, Israel’s limited withdrawals left Jewish settlements entirely undisturbed. The country had offloaded the cost of administering Palestinian population centers–its obligation as the occupying power–and reduced its exposure to Palestinian resistance without removing a single settler or even halting construction. Many Palestinian leaders understood the significance of this outcome. PLO official Dr. Hanan Ashrawi articulated her concern with characteristic clarity and prescience:

It's clear that the ones who initialed this agreement have not lived under occupation. You postponed the settlement issue and Jerusalem without even getting guarantees that Israel would not continue to create facts on the ground [settlements] that would preempt and prejudge the final outcome. And what about human rights? There's a constituency at home, a people in captivity, whose rights must be protected and whose suffering must be alleviated. What about all our red lines? Territorial jurisdiction and integrity are negated in substance and the transfer of authority is purely functional. . . . At least you should have done something about Jerusalem, settlements and human rights! Strategic issues are fine, but we know the Israelis and we know that they will exploit their power as occupier to the hilt and by the time you get around to permanent status, Israel would have permanently altered realities on the ground.4

Indeed, though Prime Minister Rabin had canceled a recently-approved development and reduced settler subsidies, settlement construction continued unabated for most of his term.

Extremists on both sides did their best to derail the talks. In February 1994, American-born Israeli Jewish Supremacist Baruch Goldstein entered the Ibrahimi Mosque in the West Bank city of Hebron and opened fire, killing 29 Palestinian worshipers. Three months later, Hamas took responsibility for a bus bombing that killed eight Israelis, kicking off a series of half a dozen bus bombings between 1994 and 1995. The most consequential terrorist attack took place on November 4th, 1995, when Yigal Amir, a Jewish settler extremist, shot Prime Minister Rabin as he left a peace rally in Tel Aviv, depriving Israel of the driving force behind its peace effort.

Rabin’s immediate successor, Shimon Peres, strongly supported a negotiated peace agreement, but a series of security missteps derailed his candidacy for the coming election. Peres’ ordered the assassination of a notorious Palestinian bomb-maker, and Hamas responded with a devastating series of reprisal attacks that left more than 50 Israelis dead.5 Peres also ordered a massive Israeli assault on militants in Lebanon that killed more than one hundred civilians, appalling Palestinian Israeli citizens who subsequently refused to vote for him in the 1996 election. Under these conditions, Benjamin Netanyahu was able to eke out a narrow victory.

Netanyahu’s Likud party opposed Palestinian statehood, but the new Prime Minister could not simply withdraw from agreements his predecessors had signed. Instead, he reinvigorated settlement growth. His “Greater Jerusalem” settlement campaign included not only accelerating construction within existing communities, but the first entirely new settlement in years, built on Palestinian land between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. This behavior decimated trust in the peace process and destroyed the legitimacy of the pro-negotiation Palestinian leadership.

Ehud Barak defeated Netanyahu in the 1999 election. Despite campaigning on a pro-peace platform, he formed a coalition government that put settler advocates in positions to fund further settlement expansion.6 During the Camp David negotiations in 2000, Palestinian officials, the CIA, the U.S. State Department, and even some Israeli intelligence officials warned that “the settlements issue, more than anything else, inflamed the [Palestinian] street.”7 That anger ignited in September 2000 when Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon visited the Haram Al-Sharif (Temple Mount) with a delegation of Likud party members and hundreds of Israeli police, a symbolic act suggesting Israeli domination of one of Islam’s holiest sites. The subsequent escalation of violence resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Israelis and thousands of Palestinians between 2000 and 2005.

As a result, Palestinian militant groups and right-wing Israeli parties grew in strength, and subsequent attempts to restart the peace process all largely failed. The Bush Administration worked with the UN, European Union, and Russia—the so-called Quartet—to implement what they called the Roadmap, which essentially proposed a ceasefire, followed by Israeli withdrawal from the cities it had recently occupied, followed by negotiation on final status issues. Neither side wanted to be seen as rejecting the plan, but both lacked the political support to follow through. By 2004, the Roadmap was widely seen as dead.8

Two additional initiatives deserve mention. The Arab Peace Initiative, which the Arab League originally ratified in 2002 and re-offered in 2007, and the deal tabled by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert in 2008. The Arab League offered Israel formal recognition and normalization of relations with all Arab countries in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from the Occupied Territories (with the potential for land swaps where agreeable) and the creation of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital. The Palestinian Authority enthusiastically supported the plan, while Hamas abstained from the vote. Israel rejected the plan in 2002, and offered a mixed reaction in 2007, but never formally responded.9

Olmert offered his plan to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas in secret. It proposed Palestinian control of Gaza and 94% of the West Bank with land swaps to compensate for the remaining 6%, and East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital, but required an international force to control the Palestinian state’s border, forbid Palestine from fielding a military, and permitted only a symbolic number of Palestinian refugees to return to Israel.10 Although Abbas reportedly expressed enthusiasm for the outline of the plan, the circumstances surrounding the offer made it difficult to accept. First, he wasn’t permitted to keep a copy of the official map and wasn’t comfortable accepting any agreement his advisors were unable to study. He was also likely wary of initiating a complex and fragile process with an unelected Israeli Prime Minister (Olmert was designated Acting Prime Minister after Ariel Sharon suffered a serious stroke) facing corruption charges and who had already announced his intention to resign. This intuition may have been prescient: Benjamin Netanyahu replaced Olmert in early 2009.

Consider the structural implications of this process. The parties attempted to negotiate agreements while unrestricted settlement construction progressively and irreversibly deepened Palestinian insecurity, destroyed the credibility of Palestinian moderates, strengthened Israeli parties that opposed a resolution, and decreased the flexibility of Israeli liberals, all without making Israeli citizens any safer. Continued settlement growth turned the peace process into the policy equivalent of running backwards on an accelerating escalator.

The consequence of the resulting failure was a catastrophic collapse of hope. Ami Ayalon was the director of Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence agency, in the late 1990s. Speaking at the Brookings Institution in 2008, he described the significant reduction in attempted terrorist attacks during his term in office, which he attributed to widespread Palestinian support for a negotiated solution with Israel. As Palestinians came to see the peace process as a sham, they increasingly supported violent resistance. When a member of the Brookings audience asked why attacks spiked in 2000 despite Prime Minister Ehud Barak’s support for negotiations, Ayalon explained his understanding of the Palestinian perspective:

If you will ask the Palestinian what happened during the 1990s, he will tell you, ‘listen, they cheated us, all of us, Israelis, Americans, everybody. They promised us that we shall have a Palestinian State, and what did they do? When we started the process in 1993 and 1994, they had 100,000 settlers’…After 6 years when the process collapsed, they saw 220,000 settlers [excluding East Jerusalem]. So instead of feeling that they are getting more and more state, they feel that they see more and more settlers, more and more checkpoints, more and more settlements, and they feel cheated.

Gaza

It was in this environment that Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian national election. Frustration with the Palestinian leadership was so widespread that even secular Palestinians voted for the Islamist party. From Ayalon’s comments at Brookings:

Only between 15 to 18 percent of the Palestinians believe in Hamas’s fundamental way of life. The rest who voted for Hamas, between 40 to 45 percent, who brought Hamas into power after the withdrawal from Gaza, did so because they came to believe first Fatah [Yasser Arafat’s party] did not deliver, diplomacy does not work, Fatah is corrupted, and Israel understands only the language of power. This was why they elected Hamas.

After Hamas won, the United States and Europe immediately suspended aid. Fatah, the incumbent Palestinian party, retained control in the West Bank as Hamas violently consolidated power in Gaza. Israel quickly tightened the blockade, destroying the local economy. It further restricted imports to only 18 essential goods after intensified rocket fire from Hamas in 2007, then cut food imports by half, and also slashed supplies of fuel and foreign currency. So began a cycle of slow humanitarian collapse, punctuated by increasingly bold Hamas attacks and overwhelming Israeli bombardment.

By the end of 2008, residents of Gaza were without power for up to 16 hours per day. Half of Gaza’s population received clean water only once per week for a few hours. Unemployment rose to nearly 50%. Hospitals experienced shortages of essential supplies.11

On November 4th of that year, the IDF broke a six-month ceasefire with a raid that killed several Hamas militants,12 and Hamas responded by firing rockets into Israel. Outgoing Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert ordered an air assault followed by a ground invasion that left roughly 1,200 Palestinians and 13 Israelis dead, and more than 100,000 Palestinians homeless. A UN special mission led by South African Justice Richard Gladstone found that both Israel and Hamas committed war crimes, including 11 episodes where it found that the Israeli Military had carried out direct attacks against civilians. The abduction and murder of three Israeli teens by Palestinians in the West Bank affiliated with Hamas triggered a similar set of events in 2014. That war left 2,300 Palestinians (about 70% civilians) and 67 Israelis (about 9% civilians) dead.13

Palestine Isolated

Netanyahu became Prime Minister again in 2009 and held the position until 2021. During this period, he leveraged the dynamics discussed above–participating in a U.S. mediated peace process while actively undermining it–to further degrade the influence of Palestinian moderates and empower their more militant competition.

In 2010, he agreed to a 10-month settlement freeze as part of peace talks with the Palestinian Authority (PA). In fact, construction continued unabated. When the freeze expired, Netanyahu refused to extend it unless the Palestinians recognized Israel as a “Jewish” state, an absurd, clearly antagonistic demand since the PLO had already recognized Israel in 1993. What business was it of theirs to take a position on Israel’s ethnic identity? The talks quickly disintegrated as Palestinian militant groups conducted a series of attacks designed to derail negotiations and settlers kept building. The Palestinian leadership looked disorganized and foolish for having engaged in the first place.

Next, Netanyahu negotiated the release of Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier Hamas abducted in 2006 while he was stationed near the border with Gaza. Under the October 2011 agreement, Israel released 1,027 Palestinians from its prisons, including Yahya Sinwar, who would go on to plan the October 7th attacks. In doing so, Netanyahu delivered an enormous political victory to Hamas just as the Palestinian Authority, led by rival Fatah party, had been gaining popularity for its effort to get the UN to recognize the State of Palestine. According to an opinion poll conducted in December of that year, 37% of Palestinians said that the prisoner swap increased their support for Hamas.

Destructive American policy and ascending right-wing politics characterize the years that followed. The Trump administration appointed an ambassador to Israel who had backed settlements both politically and financially. The Administration then announced it would relocate the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem from Tel Aviv, a break with precedent that effectively acknowledged Israel’s unilateral annexation of the city. The former President cut U.S. aid that supported security cooperation, humanitarian assistance, and even coexistence programs. In 2019, the State Department said that it no longer considers settlements illegal under international law, then had the temerity to announce a new peace plan the following year. Needless to say, Palestinians boycotted.14

Meanwhile, the Israeli government lurched farther and farther to the right. In 2019, Benjamin Netanyahu said “Israel is not a state of all its citizens. According to the basic nationality law we passed, Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people – and only it.” The law he referenced, which passed in 2018, states: “Israel is the historic homeland of the Jewish people and they have an exclusive right to national self-determination in it.” Netanyahu’s subsequent cabinet nominations have made strides to turn this law into policy. The Religious Zionist Party and Jewish Power, both Jewish supremacist parties, joined Netanyahu’s government in 2022. The current Security Minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, is the head of Jewish Power and a man who an Israeli court once convicted of supporting terrorism. He suggested after the election that Palestinians are merely guests in Israel and must be reminded who the “landlords” are, and that “the people of the left and the Arabs will continue to be afraid.” Mr. Ben-Gvir is known to keep a portrait of Baruch Goldstein, who massacred 29 Palestinian worshippers in 1994, in his living room.

Concurrently, daily life for Palestinians became increasingly brutal. In 2018, the IDF killed more than 200 Palestinians protesting the siege of Gaza near the border wall. In April of 2021, far-right Jewish protestors marched through Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem chanting “Death to Arabs”. In May of that year, protests broke out across the country in anticipation of a Israeli Supreme Court ruling expected to force six Palestinians out of their Jerusalem homes and replace them with Jewish extremists. After evening prayer on May 7, a group of Palestinian worshippers began throwing rocks at Israeli police, who then raided the Al-Aqsa Mosque, injuring hundreds of worshipers. The UN recorded 591 settler attacks on Palestinians and their property during the first half of 2023–a 39% increase from the previous year–resulting in the displacement of nearly 400 people. Palestinians killed 30 Jewish Israelis during the first three quarters of 2023. The fact that many of the perpetrators had not previously been involved in political violence prompted Israel’s domestic intelligence agency to issue a rare warning that settler violence was partly responsible for the increase in terrorism.15 209 Palestinian civilians lost their lives during the same period; the IDF killed 200 and Jewish settlers killed nine.16

The international community, distracted by Covid and Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, largely ignored these events. Netanyahu moved to solidify the status quo by trying to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia. He strongly suggested in a September 2023 interview with CNN that the two governments were close to reaching an agreement. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman seemed to indicate that this was indeed the case. Yet another Arab nation appeared prepared to recognize Israel without insisting on a final status agreement with Palestinians.

October 7th

In the early hours of a warm October morning, Hamas operatives disabled the advanced surveillance and weapons systems that surround the Gaza strip and invaded Israel by sea, land, and air. Militant groups fired hundreds of rockets into Israel as thousands of fighters poured through the border wall.17 They raided nearby military installations, residential communities, and an outdoor festival, taking 240 hostages and killing more than 1000 Israelis, the majority of whom were civilians, including 20 under the age of 15.18

The barbarity of these attacks has understandably drawn enormous attention. Murdering and kidnapping non-combatants is indisputably a war crime, and Hamas’ claim that its soldiers did not target civilians is demonstrably false. Less obvious is the strategic reasoning of the perpetrators, who clearly understood that Israel’s response would be overwhelming.

Consider that the status quo had become both intolerable and calcified. Apartheid had deepened and become the presumptive Israeli policy; diplomatic options appeared entirely exhausted; civil disobedience had become increasingly dangerous; and Netanyahu seemed to have successfully buried the entire issue. In the face of that reality, disruption was a rational approach. Short of resigning themselves to indefinite oppression, it’s unclear what other options Palestinians had.

Senior Hamas leader Khalil al-Hayya articulated exactly this logic in a November interview with the New York Times. He argued it was necessary to “change the entire equation and not just have a clash,” and that “we succeeded in putting the Palestinian issue back on the table.”

Readers should not confuse explanation with justification. There are obvious moral and tactical arguments against slaughtering civilians and triggering a predictably apocalyptic response, but failing to grasp the fundamental dynamics that motivated Hamas’s assault would be an abdication of the responsibility to understand the underlying causes of violence.

Massacre

On December 21st, The New York Times published an investigation showing that the IDF dropped 2000-pound bombs, one of the largest conventional munitions available to modern militaries, on areas it designated as safe for civilians, at least 208 times.

Those unfamiliar with this type of warfare should be assured that such behavior is not at all normal. From the Washington Post:

The evidence shows that Israel has carried out its war in Gaza at a pace and level of devastation that likely exceeds any recent conflict, destroying more buildings, in far less time, than were destroyed during the Syrian regime’s battle for Aleppo from 2013 to 2016 and the U.S.-led campaign to defeat the Islamic State in Mosul, Iraq, and Raqqa, Syria, in 2017.

The IDF explained to the Times that such munitions are necessary to reach Hamas’ tunnels. That doesn’t explain why designated safe zones were targeted, nor does it square with any reasonable interpretation of the Geneva Convention, which requires that the military value of the target must be sufficient to justify the associated harm to civilians. Such compromises could theoretically apply to the handful of Hamas leaders Israel had killed by this point in the war, yet Israel claims to have found just cause to demolish entire city blocks—to which it specifically directed civilians—at a rate of nearly three times per day.

Equally dubious is Israel’s claim that it is taking adequate measures to protect civilians. Consider the IDF’s apparent disregard for the rules of engagement. In December, Israeli soldiers killed three of the hostages they ostensibly invaded to save. They were waving white flags, shirtless (to show they were unarmed) and approaching slowly. The first two were killed immediately, the third even after he first took cover and started communicating in Hebrew. As of early January, an astonishing 20% of the IDF’s own casualties resulted from accidents and friendly fire incidents.

On February 29th, Israeli troops opened fire at hundreds of Palestinians crowding a food-aid convoy in southern Gaza, resulting in the deaths of more than 100 people. Israel said that its troops opened fire upon feeling threatened and blamed a stampede for most of the deaths, but both the Gazan health ministry and doctors on the scene reported that the vast majority of the dead and injured had suffered gunshot wounds. The New York Times published a video analysis of the incident, but said that Israel had edited out the footage showing the cause of the casualties.

Firing on civilians and indiscriminately bombing dense residential neighborhoods are perhaps the lesser of Israel’s human rights violations. The greater is Israel’s decision to cut Gaza off from access to food, water, disinfectant, tampons, electricity, and medical supplies, and to destroy almost all shelter. More than 70% of Gaza’s housing stock is no longer suitable for habitation.19 By the end of December, there had been over 369,000 reports of infectious diseases, and 50% of families reported at least one member going hungry each night.

The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs published a situation report on February 21st revealing that the Israeli military had denied access to 51% of food aid missions to northern Gaza during the first half of January. In late February, a U.N. humanitarian aid official told the Security Council that more than 500,000 Palestinians in Gaza are “one step away from famine”. Aid organization Save the Children reported that families have begun eating tree leaves and animal feed out of desperation.

Northern Gaza’s only working children's hospital reported that 15 of its patients had died of starvation as of March 3rd. Israel nevertheless continued blocking aid. A March 5th statement from The World Food Programme announced that Israel had denied its most recent attempt to deliver 200 tons of food to Northern Gaza. The Israeli agency responsible for coordinating food aid described this as a “operational decision by forces on the ground.”

To get a sense of what this manufactured hell looks like, The New York Times interviewed Samah Al-Farra, a woman in Gaza whose daughter had been begging her for food for the past few weeks. The family was living in the sandy mud of Gaza’s southern beaches without shelter. The children are covered in rashes because the only water to which they have access is filled with the refuse of war: blood, feces, bacteria. Al-Farra’s six-year-old daughter has stopped begging for food because she is too weak to speak. She’s too weak even to scratch her rashes.

She is one of lucky ones. Thousands of children have been pulled from the rubble, underwent surgery—by the light of a heroic nurse’s iPhone and without anesthesia—only to be told their whole family is dead. This is such a common phenomenon, that doctors started tracking affected children by writing “WCNSF” on their arms in sharpie: Wounded Child No Surviving Family.

The United Nations defines genocide as:

Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Intent is usually difficult to establish because people in senior positions tend not to document goals that the world may find disagreeable. Israel’s leadership does not appear to maintain such discretion. South Africa’s case against Israel in the International Court of Justice argues that Israel’s Minister of Defense, Yoav Gallant, declared the military’s intention to punish the entire population of Gaza when he said, on October 9th: “I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip. There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly.” Israel’s representatives defended these statements as “Clearly rhetorical, made in the immediate aftermath of an event that clearly traumatized Israel, but that can not be seen as demanding genocide. They express anguish.” Put more succinctly: Israel’s most senior military leader publicly stated that he ordered a complete embargo of the basics required for human life, the anticipated humanitarian catastrophe then came to pass, but the court should overlook this because “he didn’t mean it.”

Defense Minister Gallant is one of the current government’s more moderate members. Security Minister and Jewish Power leader Itamar Ben-Gvir, spoke on 28 January at a conference in Jerusalem entitled “Conference for the Victory of Israel - Settlement Brings Security: Returning to the Gaza Strip and Northern Samaria.” He called for the government to find a legal way to “voluntarily emigrate” Palestinians out of Gaza so that they could be replaced by Jewish settlers. Israel’s Minister of Communications helpfully explained that, in times of war, “’voluntary’ is a state you impose [on someone] until they give their consent.”

This nationalist bellicosity reveals the attitudes of leaders at the highest levels of government, but it is not the only cause of Israel’s behavior, and the conflict would have arrived at this juncture even without it. Israel wishes to identify as Jewish, to elect its government by popular vote, and to control territory that is home to as many Palestinans as Jews. Insisting on all three doesn’t leave it with many options beyond expulsion, apartheid, and genocide.

Expulsion may allow Israeli municipalities like Jerusalem to adjust the composition of particular neighborhoods, but it is impractical at the scale required to impact national demographics. Beyond the obvious barbarity of forcing millions of people out of their homes is the likely-insurmountable challenge of convincing other countries to accept them.

Apartheid has proved prohibitively expensive. The strain of maintaining direct occupation in the West Bank alone was already so significant that it motivated the redeployments that left the Gaza border so understaffed on October 7th.20 Even if those troops had not been reassigned, Israel would have needed an order of magnitude more personnel to prevent Hamas’ assault. New York Times correspondent Ronen Bergman asked a “very high-ranked official in [Israel’s] southern front” what he would do if he had known that Hamas was capable of the October 7th attack. The official responded that Israel would need to station a massive force, roughly 20,000 troops, on the border with Gaza year-round.

That ultimately leaves genocide. Killing on such a massive scale might have been postponed if Netanyahu had set more modest objectives, negotiated the release of more hostages, and reinforced the border, but it could not have been avoided. Militancy always persists in the absence of alternatives, and anything that persists adapts. The very act of distinguishing between military and civilian targets eventually forces militants to eliminate such distinction. There therefore isn’t a clear line between disabling armed groups and destroying all of society; it’s a continuum. The absence of a political solution forces Israel further along that continuum.

Where We’ve Arrived

Famine, disease, and destitution will define life in Gaza during the years following an eventual ceasefire. Militant resistance groups will quietly rebuild, even in the unlikely event that Israel eliminates Hamas. They will recruit legions of outraged, traumatized young men by offering them opportunities for revenge: hope’s only available relative. Meanwhile, young Israelis will drive their government farther to the right, and the settlements will continue their tireless march across the landscape.

American and European officials nevertheless continue to double down on the same formula that has kept us on this cataclysmic trajectory: call for the creation of a Palestinian state while permitting settlement growth and continuing to arm Israel with alacrity. Where do we think this will lead?

The failure of the U.S. and Europe to impose on Israel, diplomatically and economically, the real cost of its colonial ambitions has already forced thousands of innocent Palestinians and Israelis to pay that cost with their lives. They will continue to do so as long as Western powers refuse to consider any policy that might force Israel to begin removing settlements. Sanctions, for example, are clearly suited to influencing the behavior of voters in a market economy like Israel’s without compromising their physical security, yet they remain completely absent from the discussion.

This conclusion is torturously obvious, perhaps even extraneous, to readers who already reject the concept of a state dedicated to one particular ethnic group, particularly when it has meant the violent dispossession of their people. For those whose grandmother survived Auschwitz, not Deir Yassin; who carry anxiety to a synagogue in Pittsburg, not a Mosque in Hebron, the notion of putting such coercive pressure on Israel may remain unthinkable. But a country that commits the same atrocities that haunt your history can never be a reliable refuge. No amount of military force can indefinitely contain millions of human beings, who eventually will, like water under pressure, burst violently through whatever seam they can find.

John Quigley, Loan Guarantees, Israeli Settlements, and Middle East Peace, 25 Vanderbilt Law Review 547 (1992) p. 554 - https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vjtl/vol25/iss4/1

"Jerusalem Municipal Data Reveals Stark Israeli-Palestinian Discrepancy in Construction Permits in Jerusalem." Peace Now, 12 Sept. 2019, https://peacenow.org.il/en/jerusalem-municipal-data-reveals-stark-israeli-palestinian-discrepancy-in-construction-permits-in-jerusalem.

Quandt, William B. Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967. University of California Press - A. Kindle Edition., Location 5100.

Ashrawi, Hanan. This Side of Peace. Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 260.

Quandt, William B. Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967. University of California Press - A. Kindle Edition., Location 6358.

Swisher, Clayton E. The Truth About Camp David: The Untold Story About the Collapse of the Middle East Peace Process (Nation Books). Kindle Edition. p. 23

Swisher, Clayton E. The Truth About Camp David: The Untold Story About the Collapse of the Middle East Peace Process (Nation Books). Kindle Edition. p. 32

Quandt, William B. Peace Process: American Diplomacy and the Arab-Israeli Conflict since 1967. University of California Press - A. Kindle Edition., Location 7542.

"Arab Peace Initiative." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arab_Peace_Initiative. Accessed 19 March, 2024.

"Ehud Olmert's Peace Offer." Jewish Virtual Library, American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ehud-olmert-s-peace-offer.

"Gaza Humanitarian Situation Report: The Impact of the Blockade on the Gaza Strip – A Human Dignity Crisis." United Nations, 15 Dec. 2008, https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-209698/.

Zanotti, Jim, et al. "Israel and Hamas: Conflict in Gaza (2008-2009)." Congressional Research Service, 19 Feb. 2009, www.crs.gov, R40101. p. 6 - https://sgp.fas.org/crs/mideast/R40101.pdf

"2014 Gaza War." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2014_Gaza_War. Accessed 20 March, 2024.

Berger, Miriam. "Timeline: Trump's Policies Toward Palestinians." The Washington Post, 29 Jan. 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/01/28/timeline-trumps-policies-toward-palestinians/.

Fabian, Emanuel. "IDF spokesman says settler violence fueling Palestinian terrorism." The Times of Israel, 7 Aug. 2023, www.timesofisrael.com/idf-spokesman-says-settler-violence-fueling-palestinian-terrorism/.

"Data on Casualties." OCHA oPt, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, www.ochaopt.org/data/casualties.

Swaine, Jon, et al. "How Hamas breached Israel’s ‘Iron Wall’." The Washington Post, 9 Oct. 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2023/11/17/how-hamas-breached-israel-iron-wall/.

"Israel Social Security Data Reveals True Picture of Oct 7 Deaths." France 24, 15 Dec. 2023, www.france24.com/en/live-news/20231215-israel-social-security-data-reveals-true-picture-of-oct-7-deaths.

"UN rights expert condemns ‘systematic’ war-time mass destruction of homes." UN News, United Nations, 5 March 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/03/1147272.

Nakhoul, Samia, and Jonathan Saul. "How Israel Was Duped as Hamas Planned Devastating Assault." Reuters, 8 Oct. 2023, www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/how-israel-was-duped-hamas-planned-devastating-assault-2023-10-08/.